Selected projects of the leads group

- How age and gender diversity shape language change

-

In this project, we look at how age and gender diversity shape the process of language formation and innovation.

This Project is lead by PhD student Lewis Ching-Yat Cheung, under the supervision of Dr. Limor Raviv and Prof. Simon Kirby.

Background:

One of the most intriguing findings in sociolinguistics is that speakers’ gender and age can affect the process of language change. Specifically, it was suggested that women are actually the leaders of language change: some studied show that women are often more linguistically innovative than men, and tend to adopt new variants more frequently. Similarly, studies show that teenagers (around the age of seventeen) also tend to create and adopt new variants much more often than adults. While this might make sense in the case of teenagers, who are in this special social position of trying to discover their unique identity and separate themselves from their parents, it is much less clear why this would be the case for women: is it about their social status, their personalities, or something else? At this point we just don’t know. This is also because, at the moment, claims regarding the role of gender and age are only based on several case studies that looked at language change post-hoc, and have never been tested experimentally or computationally before. This means that we currently don’t know how population differences in gender and age influence language evolution, innovation, and change, and whether different linguistic tendencies are actually associated with male vs. female speakers and adult vs. teen speakers in the lab.

The goal of the project:

This project will couple experimental methods and computational modelling to determine whether women and adolescents really lead the process of language change from the initial stages of emergence. Specifically, we will use group communication experiments and simulated populations of hierarchal Bayesian agents, and manipulate the composition of mini-societies in terms of the gender and age of individuals. Will such changes in the identity of group members influence the creation and spread of linguistic norms over time? And is it really the case that women and teenagers are more likely to create and adopt novel words, as was suggested by previous theories?

In addition, we also plan to run several other more controlled experiments to look at age and gender effects on priming and accommodation, in order to test the mechanisms that are said to underlie these effects in the real-world. This will allow us to see how individual traits actually build up to a population-level phenomena, and can provide really valuable insights by breaking down a very complex process into smaller and more transparent steps.

- Language emergence with deep learning AIs

-

In this project, we look at language emergence with artificial neural netorks and ask how can we ancour deep learning models in human data and linguistics theory.

This project is led by postdoctoral researcher Dr. Lukas Galke, under the guidance of Dr. Limor Raviv and Dr. Yoav Ram.

The idea is to take the patterns obtained from real groups of human participants during group communication studies, and compare them to patterns obtained from different-sized populations of interacting artificial agents - who are doing exactly the same task as the humans did in the lab. This will allow us to develop a close model of participants’ behavior using deep learning.

This will allow to ask questoins like: which model architecture best simulates the human data? What kind of memory cap or innovation protocols do we need to set in place to mimic the results we see with real participants? And so on. This will inform both our understanding of AIs themselves (e.g., what kind of structure is most cognitively and communicatively plausible?) and our understanding of our own participants (e.g., what kind of memory limitations best captures their behaviors).

- Multimodal language evolution and adaptaion using Virtual Reality

-

The goal of this project is to compare the speed and nature of language evolution in different modalities, and to test how these different modalities may adapt to different environmental conditions.

This project is led by Master students Luisa Wolf and Kotryna Motiekaityte under the supervision of Dr. Limor Raviv, in collaboration with Dr. Markus Perlman, Dr. David Peeter, Dr. Gerardo Ortega, and Dr. Hans-Rutger Bosker.

Specifically, we compare the process of language formation during communication when using gestures vs. vocalizations, or both. This is important because scientists have long been arguing whether the first languages were signed or spoken or a combination of the two? At the moment, we just don’t know...

But by looking at how gestural and vocal languages are formed in the VR environment, we can examine the multimodal origin of language and ask: what are the comparative advantages and disadvantages of each modality during the emergence of a novel communication system?

Once we understand these better and establish the default patterns for each modality, we can also examine questions related to language diversity, and specifically, how aspects of the physical environment shape languages? One thing that may cause languages to be different is the fact that they are spoken in different environments (e.g., mountains, deserts, tropical climates), and this can affect what kind of languages will evolve in that region. For example, it has been shown that languages spoken in dry and cold climates are less likely to develop a tonal distinction between words - probably because in such dry climates, it can be harder to control your tone of voice. This shows that languages can adapt to their enviorments.

In this project, we will test what happens if we add environmental challenges to each modality - Would adaptations occur? Would introducing adverse environmental conditions affect the phonology and grammar of languages in different modalities? In particular, the plan is to would introduce poor lighting and visibility to the VR environment and/or “wind” by playing a sound on the speakers that masks the /s/ sound. In this case, the prediction is that: 1. signed languages will adapt to the poor lighting by making gestures larger and more salient; and 2. that under noisy windy conditions, the vocal languages would evolve include less fricative sounds or even not at all, since these would be hard to detect.

Together, This would be the first direct evidence that the phonology and the basic building blocks of language can be affected by the environment.

- Language Evolution with Swarm Robotics

-

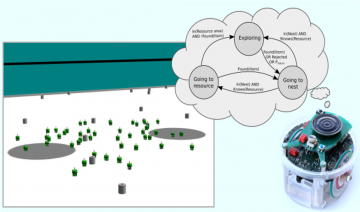

In this project, we are using swarm robotics models to see if we can mimics some patterns of emergent communication with humans. In these simulations, robots from different nests are engaged in a foraging task (gathering resources in their environment) while playing a language game.

This project is led by Dr. Nicolas Cambier and PhD student Roman Miletitch, under the guidance of Dr. Limor Raviv and Prof. Antonio Benítez-Burraco.

Crucially, we introduce two novel features to these models, that are very important for understanding the behavior of social animals like humans, but that are currently missing from swarm robotics simulations: (1) robot individuation: robots have a partner-specificity memory, keeping track of the outcomes of past interactions with specific robots; (2) Dynamic prosociality: robots’ tendency to interact with another robots is based on their shared experience, such that successful communications between robots reduces their aggression toward each other, and increase their chance to interact again.

Introducing these features leads to the formation of a classic “in-group bias” known from social science, where robots favor interaction with some robots over others - a bias which is highly common in social animals in nature, but was so far absent from swarm robotics models.

With this novel addition, swarm robots can now prove to be a very useful approach for testing big hypotheses in the field of language evolution. Specifically, we plan to test the self-domestication hypothesis - which suggests that evolutionary pressures towards reduced aggression and increased prosociality (and especially towards non-kin and strangers), may be responsible for many of humans’ unique traits, including language.

- Elephants as a new animal model for cultural evolution

-

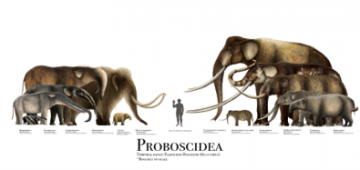

This project looks at Elephants as a potentially new animal model for studying cultural and language evolution. Specifically, we propose that elephants, like humans, may have also undergone a process of self-domestication early on in their evolution.

This project is led by Dr. Limor Raviv, in collaboration with Dr. Joshua Plotnik, PhD student Sarah Jacobson, Dr. Vincent Lynch, Jacob Bowman and Prof. Antonio Benítez-Burraco.

To support this hypothesis, we use extensive cross-species comparisons to show that Elephants indeed exhibit many of the features that are typically associated with self-domestication, such as reduced aggression, increased prosociality, extended juvenille period, enahced play behavior, reduce skull and teeth size, socially regulated cortisol levels, vocal learning, complex multimodal communication - and many more. We also show that Elephnats possess many of the prerequisites associated with cultural evolution, including social learning, tool use, theory of mind, and complex community structure.

We also use novel genetic analyses to show that several candidate genes that were previously associated with self-domestication have been positively selected and enriched in elephants, and discuss several possible explanations for what may have triggered a self-domestication process in the elephant lineage.

Since the only other species so far that has been identified as self-domesticated besides humans are Bonobos (which are also primates), and since the most recent common ancestor of humans and elephants is likely the most recent common ancestor of all placental mammals, this research opens the door for exciting new insights on convergent evolution, going far beyond the primate family.

- Language learning biases in Children with and without DLD

-

In this project, we ask whether children and adults benefit from systematic structure in a similar fashion while learning an artificial language, and test whether there are any correlation between learning behavior and cognitive abilities such as working memory and selective attention.

This project is led by research fellow Dr. Imme Lammertink, in collaboration with Dr. Limor Raviv, PhD student Marianne de Heer Kloots, and Master student Mary Bazioni.

Background

Cross-linguistic differences in morphological complexity could have important consequences for language learning. Specifically, it is often assumed that languages with more regular, compositional, and transparent grammars are easier to learn by both children and adults. This suggests that some languages are acquired faster than others, and that this advantage can be traced back to the degree of systematicity in the language. However, the causal relationship between systematic linguistic structure and language learnability is poorly attested, despite its importance for theories on language evolution, second language learning, and the origin of linguistic diversity.

The Current Project

The goal of this project is to extend the previous findings to language acquisition by children, and ask: (a) whether more structured languages are easier to learn by children in the same way as adults? and (b) whether there is a correlation between learning behavior and other cognitive capacities important for language learning such as working memory and selective attention. Specifically, this study will experimentally test the effects of systematic structure on language learning and generalization by examining children’s learning of different artificial languages that vary in their degree of systematic structure, and then compare their performance to that of adults. In addition, we plan to measure children’s and adults’ working memory and selective attention in order to examine the relationship between these factors and learnability effects.

Share this page